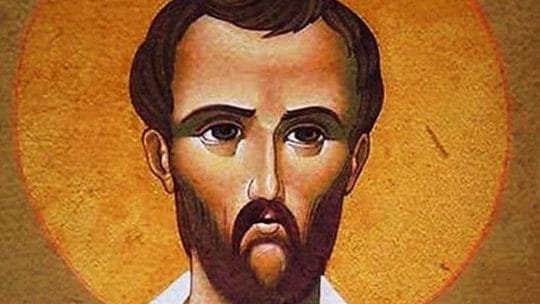

POPE BENEDICT XVI ON ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM

Throughout the year, the liturgy presents to us as examples holy ministers of the Altar who have drawn strength from the imitation of Christ in daily intimacy with him in the celebration and adoration of the Eucharist. A few days ago, we commemorated Saint John Chrysostom, Patriarch of Constantinople at the end of the fourth century. He was described as “golden-mouthed” because of his extraordinary eloquence; he was also called “Doctor of the Eucharist” because of the vastness and depth of his teaching on the Most Holy Sacrament. The “Divine Liturgy” which is most frequently celebrated in the Eastern Church and which bears his name as well as his motto: “a man full of zeal suffices to transform a people”, shows the effectiveness of Christ’s action through his ministers.

(General Audience,18 September 2005)

It can be said that John of Antioch, nicknamed “Chrysostom”, that is, “golden-mouthed”, because of his eloquence, is also still alive today because of his works. An anonymous copyist left in writing that “they cross the whole globe like flashes of lightening.” Chrysostom’s writings also enable us, as they did the faithful of his time whom his frequent exiles deprived of his presence, to live with his books, despite his absence. This is what he himself suggested in a letter when he was in exile (To Olympias, Letter 8, 45).

He was born in about the year 349 A.D. in Antioch, Syria (today Antakya in Southern Turkey). He carried out his priestly ministry there for about eleven years, until 397, when, appointed Bishop of Constantinople, he exercised his episcopal ministry in the capital of the Empire prior to his two exiles, which succeeded one close upon the other—in 403 and 407. Let us limit ourselves today to examining the years Chrysostom spent in Antioch.

He lost his father at a tender age and lived with Anthusa, his mother, who instilled in him exquisite human sensitivity and a deep Christian faith. After completing his elementary and advanced studies crowned by courses in philosophy and rhetoric, he had as his teacher Libanius, a pagan and the most famous rhetorician of that time. At his school John became the greatest orator of late Greek antiquity. He was baptized in 368 and trained for the ecclesiastical life by Bishop Meletius, who instituted him as lector in 371. This event marked Chrysostom’s official entry into the ecclesiastical cursus. From 367 to 372, he attended the Asceterius, a sort of seminary in Antioch, together with a group of young men, some of whom later became Bishops, under the guidance of the exegete Diodore of Tarsus, who initiated John into the literal and grammatical exegesis characteristic of Antiochean tradition.

He then withdrew for four years to the hermits on the neighboring Mount Silpius. He extended his retreat for a further two years, living alone in a cave under the guidance of an “old hermit”. In that period, he dedicated himself unreservedly to meditating on “the laws of Christ”, the Gospels, and especially the Letters of Paul. Having fallen ill, he found it impossible to care for himself unaided and therefore had to return to the Christian community in Antioch (cf. Palladius, Dialogue on the Life of Saint John Chrysostom 5). The Lord, his biographer explains, intervened with the illness at the right moment to enable John to follow his true vocation. In fact, he himself was later to write that were he to choose between the troubles of Church government and the tranquility of monastic life, he would have preferred pastoral service a thousand times (cf. On the Priesthood 6, 7): it was precisely to this that Chrysostom felt called. It was here that he reached the crucial turning point in the story of his vocation: a full-time pastor of souls! Intimacy with the Word of God, cultivated in his years at the hermitage, had developed in him an irresistible urge to preach the Gospel, to give to others what he himself had received in his years of meditation. The missionary ideal thus launched him into pastoral care, his heart on fire.

Between 378 and 379, he returned to the city. He was ordained a deacon in 381 and a priest in 386 and became a famous preacher in his city’s churches. He preached homilies against the Arians, followed by homilies commemorating the Antiochean martyrs and other important liturgical celebrations: this was an important teaching of faith in Christ and also in the light of his saints. The year 387 was John’s “heroic year”, that of the so-called “revolt of the statues”. As a sign of protest against levied taxes, the people destroyed the Emperor’s statues. It was in those days of Lent and the fear of the Emperor’s impending reprisal that Chrysostom gave his twenty-two vibrant Homilies on the Statues, whose aim was to induce repentance and conversion. This was followed by a period of serene pastoral care (387-397).

Chrysostom is among the most prolific of the Fathers: seventeen treatises, more than seven hundred authentic homilies, commentaries on Matthew and on Paul (Letters to the Romans, Corinthians, Ephesians, and Hebrews), and 241 letters are extant. He was not a speculative theologian. Nevertheless, he passed on the Church’s tradition and reliable doctrine in an age of theological controversies, sparked above all by Arianism or, in other words, the denial of Christ’s divinity. He is therefore a trustworthy witness of the dogmatic development achieved by the Church from the fourth to the fifth centuries. His is a perfectly pastoral theology in which there is constant concern for consistency between thought expressed via words and existential experience. It is this in particular that forms the main theme of the splendid catecheses with which he prepared catechumens to receive Baptism. On approaching death, he wrote that the value of man lies in “exact knowledge of true doctrine and in rectitude of life” (Letter from Exile). Both these things, knowledge of truth and rectitude of life, go hand in hand: knowledge has to be expressed in life. All his discourses aimed to develop in the faithful the use of intelligence, of true reason, in order to understand and to put into practice the moral and spiritual requirements of faith.

John Chrysostom was anxious to accompany his writings with the person’s integral development in his physical, intellectual, and religious dimensions. The various phases of his growth are compared to as many seas in an immense ocean: “The first of these seas is childhood” (Homily 81, 5 on Matthew’s Gospel). Indeed, “it is precisely at this early age that inclinations to vice or virtue are manifest.” Thus, God’s law must be impressed upon the soul from the outset “as on a wax tablet” (Homily 3, 1 on John’s Gospel): This is indeed the most important age. We must bear in mind how fundamentally important it is that the great orientations which give man a proper outlook on life truly enter him in this first phase of life. Chrysostom therefore recommended: “From the tenderest age, arm children with spiritual weapons and teach them to make the Sign of the Cross on their forehead with their hand” (Homily, 12, 7 on First Corinthians). Then come adolescence and youth: “Following childhood is the sea of adolescence, where violent winds blow. . . . for concupiscence . . . grows within us” (Homily 81, 5 on Matthew’s Gospel). Lastly comes engagement and marriage: “Youth is succeeded by the age of the mature person who assumes family commitments: this is the time to seek a wife” (ibid.). He recalls the aims of marriage, enriching them—referring to virtue and temperance—with a rich fabric of personal relationships. Properly prepared spouses therefore bar the way to divorce: everything takes place with joy, and children can be educated in virtue. Then when the first child is born, he is “like a bridge; the three become one flesh, because the child joins the two parts” (Homily 12, 5 on the Letter to the Colossians), and the three constitute “a family, a Church in miniature” (Homily 20, 6 on the Letter to the Ephesians).

Chrysostom’s preaching usually took place during the liturgy, the “place” where the community is built with the Word and the Eucharist. The assembly gathered here expresses the one Church (Homily 8, 7 on the Letter to the Romans), the same Word is addressed everywhere to all (Homily 24, 2 on First Corinthians), and Eucharistic Communion becomes an effective sign of unity (Homily 32, 7 on Matthew’s Gospel). His pastoral project was incorporated into the Church’s life, in which the lay faithful assume the priestly, royal, and prophetic office with Baptism. To the lay faithful he said: “Baptism will also make you king, priest, and prophet” (Homily 3, 5 on Second Corinthians). From this stems the fundamental duty of the mission, because each one is to some extent responsible for the salvation of others: “This is the principle of our social life . . . not to be solely concerned with ourselves!” (Homily 9, 2 on Genesis). This all takes place between two poles: the great Church and the “Church in miniature”, the family, in a reciprocal relationship. As you can see, dear brothers and sisters, Chrysostom’s lesson on the authentically Christian presence of the lay faithful in the family and in society is still more timely than ever today. Let us pray to the Lord to make us docile to the teachings of this great Master of the faith.

(General Audience, 19 September 2007)

Stay updated: subscribe by email for free TO OUR NEW WEBSITE www.catholicsstrivingforholiness.org (PUT YOUR EMAIL IN THE SUBSCRIBE WIDGET).

We are also in www.fb.com/Catholicsstrivingforholiness. Kindly help more people in their Christian life by liking our page and inviting your family, friends and relatives to do so as well. Thanks in advance and God bless you and your loved ones! Fr. Rolly Arjonillo