January 2:

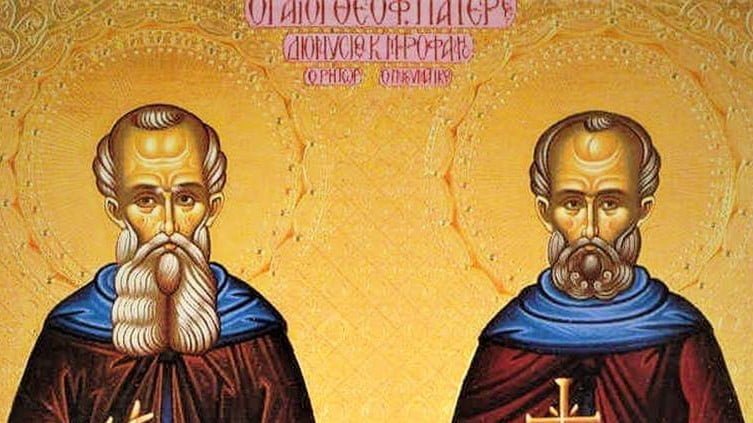

Sts. Basil the Great

and Gregory Nazianzen, Bishops and Doctors of the Church

St. Basil became bishop of Caesarea in 370. The monks of the Eastern Church today still follow the monastic rules which he set down.

St. Gregory (330-390) was also from Cappadocia. A friend of Basil, he too followed the monastic way of life for some years. He was ordained priest and in 381 became bishop of Constantinople.

Together with St. Gregory of Nyssa, Basil’s brother, they made major contributions to the definition of the Most Holy Trinity finalized at the First Council of Constantinople in 381 and to the final version of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed.

POPE BENEDICT ON ST. BASIL THE GREAT

One of the great Fathers of the Church, Saint Basil, [was] described by Byzantine liturgical texts as “a luminary of the Church”. He was an important Bishop in the fourth century to whom the entire Church of the East, and likewise the Church of the West, looks with admiration because of the holiness of his life, the excellence of his teaching, and the harmonious synthesis of his speculative and practical gifts. He was born in about 330 A.D. into a family of saints, “a true domestic Church”, immersed in an atmosphere of deep faith. He studied with the best teachers in Athens and Constantinople. Unsatisfied with his worldly success and realizing that he had frivolously wasted much time on vanities, he himself confessed: “One day, like a man roused from deep sleep, I turned my eyes to the marvelous light of the truth of the Gospel. . . . and I wept many tears over my miserable life” (cf. Letter 223: PG 32, 824a). Attracted by Christ, Basil began to look and listen to him alone (cf. Moralia 80, 1: PG 31, 86obc). He devoted himself with determination to the monastic life through prayer, meditation on the Sacred Scriptures and the writings of the Fathers of the Church, and the practice of charity (cf. Letters 2, 22), also following the example of his sister, Saint Macrina, who was already living the ascetic life of a nun. He was then ordained a priest and finally, in the year 370, Bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia in present-day Turkey.

Through his preaching and writings, he carried out immensely busy pastoral, theological, and literary activities. With a wise balance, he was able to combine service to souls with dedication to prayer and meditation in solitude. Availing himself of his personal experience, he encouraged the foundation of numerous “fraternities”, in other words, communities of Christians consecrated to God, which he visited frequently (cf. Gregory Nazianzen, Oratio 43, 29, in laudem Basilii: PG 36, 536b). He urged them with his words and his writings, many of which have come down to us (cf. Regulae brevius tractatae, Proemio: PG 31, 1080ab), to live and to advance in perfection. Various legislators of ancient monasticism drew on his works, including Saint Benedict, who considered Basil his teacher (cf. Rule 73, 5). Indeed, Basil created a very special monasticism: it was not closed to the community of the local Church but instead was open to it. His monks belonged to the particular Church; they were her life-giving nucleus and, going before the other faithful in the following of Christ and not only in faith, showed a strong attachment to him—love for him—especially through charitable acts. These monks, who ran schools and hospitals, were at the service of the poor and thus demonstrated the integrity of Christian life. In speaking of monasticism, the Servant of God John Paul II wrote: “For this reason many people think that the essential structure of the life of the Church, monasticism, was established, for all time, mainly by Saint Basil; or that, at least, it was not defined in its more specific nature without his decisive contribution” (Apostolic Letter Patres Ecclesiae, no. 2, January 1980; L’Osservatore Romano English edition, 25 February, p. 6).

As the Bishop and Pastor of his vast Diocese, Basil was constantly concerned with the difficult material conditions in which his faithful lived; he firmly denounced the evils; he did all he could on behalf of the poorest and most marginalized people; he also intervened with rulers to alleviate the sufferings of the population, especially in times of disaster; he watched over the Church’s freedom, opposing even the powerful in order to defend the right to profess the true faith (cf. Gregory Nazianzen, Oratio 43, 48-51 in laudem Basilii: PG 36, 557c—561c). Basil bore an effective witness to God, who is love and charity, by building for the needy various institutions (cf. Basil, Letter 94: PG 32, 488 bc), virtually a “city” of mercy, called “Basiliade” after him (cf. Sozomeno, Historia Eccl. 6, 34: PG 67, 1397a). This was the origin of the modern hospital structures where the sick are admitted for treatment.

Aware that “the liturgy is the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed”, and “also the fount from which all her power flows” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, no. 10), and in spite of his constant concern to do charitable acts, which is the hallmark of faith, Basil was also a wise “liturgical reformer” (cf. Gregory Nazianzen, Oratio 43, 34 in laudem Basilii: PG 36, 541 c). Indeed, he has bequeathed to us a great Eucharistic Prayer [or anaphora] which takes its name from him and has given a fundamental order to prayer and psalmody: at his prompting, the people learned to know and love the Psalms and even went to pray them during the night (cf. Basil, In Psalmum 1, 1-2: PG 29, 212a—213c). And we thus see how liturgy, worship, prayer with the Church, and charity go hand in hand and condition one another.

With zeal and courage, Basil opposed the heretics who denied that Jesus Christ, like the Father, was God (cf. Basil, Letter 9, 3: PG 32, 272a; Letter 52, 1-3: PG 32, 392b-396a; Adv. Eunomium 1, 20: PG 29, 556c). Likewise, against those who would not accept the divinity of the Holy Spirit, he maintained that the Spirit is also God and “must be equated and glorified with the Father and with the Son” (cf. De Spiritu Sancto: SC 17ff., 348). For this reason Basil was one of the great Fathers who formulated the doctrine on the Trinity: the one God, precisely because he is love, is a God in three Persons who form the most profound unity that exists: divine unity.

In his love for Christ and for his Gospel, the great Cappadocian also strove to mend divisions within the Church (cf. Letters 70, 243), doing his utmost to bring all to convert to Christ and to his Word (cf. De Iudicio 4: PG 31, 660b-661a), a unifying force which all believers were bound to obey (cf. ibid., 1-3: PG 31, 653a-656c).

To conclude, Basil spent himself without reserve in faithful service to the Church and in the multiform exercise of the episcopal ministry. In accordance with the program that he himself drafted, he became an “apostle and minister of Christ, steward of God’s mysteries, herald of the Kingdom, a model and rule of piety, an eye of the Body of the Church, a Pastor of Christ’s sheep, a loving doctor, father, and nurse, a cooperator of God, a farmer of God, a builder of God’s temple” (cf. Moralia 80, 11-20: PG 31, 864b-868b).

This is the program which the holy Bishop consigns to preachers of the Word—in the past as in the present—a program which he himself was generously committed to putting into practice. In 379 A.D. Basil, who was not yet fifty, returned to God “in the hope of eternal life, through Jesus Christ Our Lord” (De Baptismo 1, 2, 9). He was a man who truly lived with his gaze fixed on Christ. He was a man of love for his neighbor. Full of the hope and joy of faith, Basil shows us how to be true Christians.

SOURCE: http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20070704.html AND http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20070801.html

POPE BENEDICT ON ST. GREGORY NAZIANZEN

Like Basil, [Gregory Nazianzen] too was a native of Cappadocia. As a distinguished theologian, orator, and champion of the Christian faith in the fourth century, he was famous for his eloquence, and as a poet, he also had a refined and sensitive soul.

Gregory was born into a noble family in about A.D. 330, and his mother consecrated him to God at birth. After his education at home, he attended the most famous schools of his time: he first went to Caesarea in Cappadocia, where he made friends with Basil, the future Bishop of that city, and went on to stay in other capitals of the ancient world, such as Alexandria, Egypt, and in particular Athens, where once again he met Basil (cf. Orationes 43:14-24: SC 384, 146-80). Remembering this friendship, Gregory was later to write: “Then not only did I feel full of veneration for my great Basil because of the seriousness of his morals and the maturity and wisdom of his speeches, but he induced others who did not yet know him to be like him. . . . The same eagerness for knowledge motivated us. . . . This was our competition: not who was first, but who allowed the other to be first. It seemed as if we had one soul in two bodies” (Orationes 43:16, 20: SC 384, 154-56, 164). These words more or less paint the self-portrait of this noble soul. Yet, one can also imagine how this man, who was powerfully cast beyond earthly values, must have suffered deeply for the things of this world.

On his return home, Gregory received Baptism and developed an inclination for monastic life: solitude as well as philosophical and spiritual meditation fascinated him. He himself wrote:

Nothing seems to me greater than this: to silence one’s senses, to emerge from the flesh of the world, to withdraw into oneself, no longer to be concerned with human things other than what is strictly necessary; to converse with oneself and with God, to lead a life that transcends the visible; to bear in one’s soul divine images, ever pure, not mingled with earthly or erroneous forms; truly to be a perfect mirror of God and of divine things, and to become so more and more, taking light from light. . .; to enjoy, in the present hope, the future good, and to converse with angels; to have already left the earth even while continuing to dwell on it, borne aloft by the spirit. (Orationes 2:7: SC 247, 96)

As he confides in his autobiography (cf. Carmina [historica] 2:1, De Vita Sua 340-49: PG 37, 1053), he received priestly ordination with a certain reluctance, for he knew that he would later have to be a Bishop, to look after others and their affairs, hence, could no longer be absorbed in pure meditation. However, he subsequently accepted this vocation and took on the pastoral ministry in full obedience, accepting, as often happened to him in his life, to be carried by Providence where he did not wish to go (cf. Jn 21:18). In 371, his friend Basil, Bishop of Caesarea, against Gregory’s own wishes, desired to ordain him Bishop of Sasima, a strategically important locality in Cappadocia. Because of various problems, however, he never took possession of it and instead stayed on in the city of Nazianzus.

In about 379, Gregory was called to Constantinople, the capital, to head the small Catholic community faithful to the Council of Nicaea and to belief in the Trinity. The majority adhered instead to Arianism, which was “politically correct” and viewed by emperors as politically useful. Thus, he found himself in a condition of minority, surrounded by hostility. He delivered five Theological Orations (Orationes 27-31: SC 250, 70-343) in the little Church of the Anastasis precisely in order to defend the Trinitarian faith and to make it intelligible. These discourses became famous because of the soundness of his doctrine and his ability to reason, which truly made clear that this was the divine logic. And the splendor of their form also makes them fascinating today. It was because of these orations that Gregory acquired the nickname: “The Theologian”. This is what he is called in the Orthodox Church: the “Theologian”. And this is because to his way of thinking theology was not merely human reflection or, even less, only a fruit of complicated speculation, but rather sprang from a life of prayer and holiness, from a persevering dialogue with God. And in this very way he causes the reality of God, the mystery of the Trinity, to appear to our reason. In the silence of contemplation, interspersed with wonder at the marvels of the mystery revealed, his soul was engrossed in beauty and divine glory.

While Gregory was taking part in the Second Ecumenical Council in 381, he was elected Bishop of Constantinople and presided over the Council; but he was challenged straightaway by strong opposition, to the point that the situation became untenable. These hostilities must have been unbearable to such a sensitive soul. What Gregory had previously lamented with heartfelt words was repeated: “We have divided Christ, we who so loved God and Christ! We have lied to one another because of the Truth, we have harbored sentiments of hatred because of Love, we are separated from one another” (Orationes 6:3: SC 405, 128). Thus, in a tense atmosphere, the time came for him to resign. In the packed cathedral, Gregory delivered a farewell discourse of great effectiveness and dignity (cf. Orationes 42: SC 384, 48-114). He ended his heartrending speech with these words: “Farewell, great city, beloved by Christ. . . . My children, I beg you, jealously guard the deposit [of faith] that has been entrusted to you (cf. 1 Tm 6:20); remember my suffering (cf. Col 4:18). May the grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ be with you all” (cf. Orationes 42:27: SC 384, 112-14).

Gregory returned to Nazianzus and for about two years devoted himself to the pastoral care of this Christian community. He then withdrew definitively to solitude in nearby Arianzo, his birthplace, and dedicated himself to studies and the ascetic life. It was in this period that he wrote the majority of his poetic works and especially his autobiography: the De Vita Sua, a reinterpretation in verse of his own human and spiritual journey, an exemplary journey of a suffering Christian, of a man of profound interiority in a world full of conflicts. He is a man who makes us aware of God’s primacy and, hence, also speaks to us, to this world of ours: without God, man loses his grandeur; without God, there is no true humanism. Consequently, let us, too, listen to this voice and seek to know God’s Face. In one of his poems he wrote, addressing himself to God: “May you be benevolent, you, the hereafter of all things” (Carmina [dogmatica] 29: PG 37, 508). And in 390, God welcomed into his arms this faithful servant who had defended him in his writings with keen intelligence and had praised him in his poetry with such great love.

SOURCE: http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20070808.html AND http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20070822.html